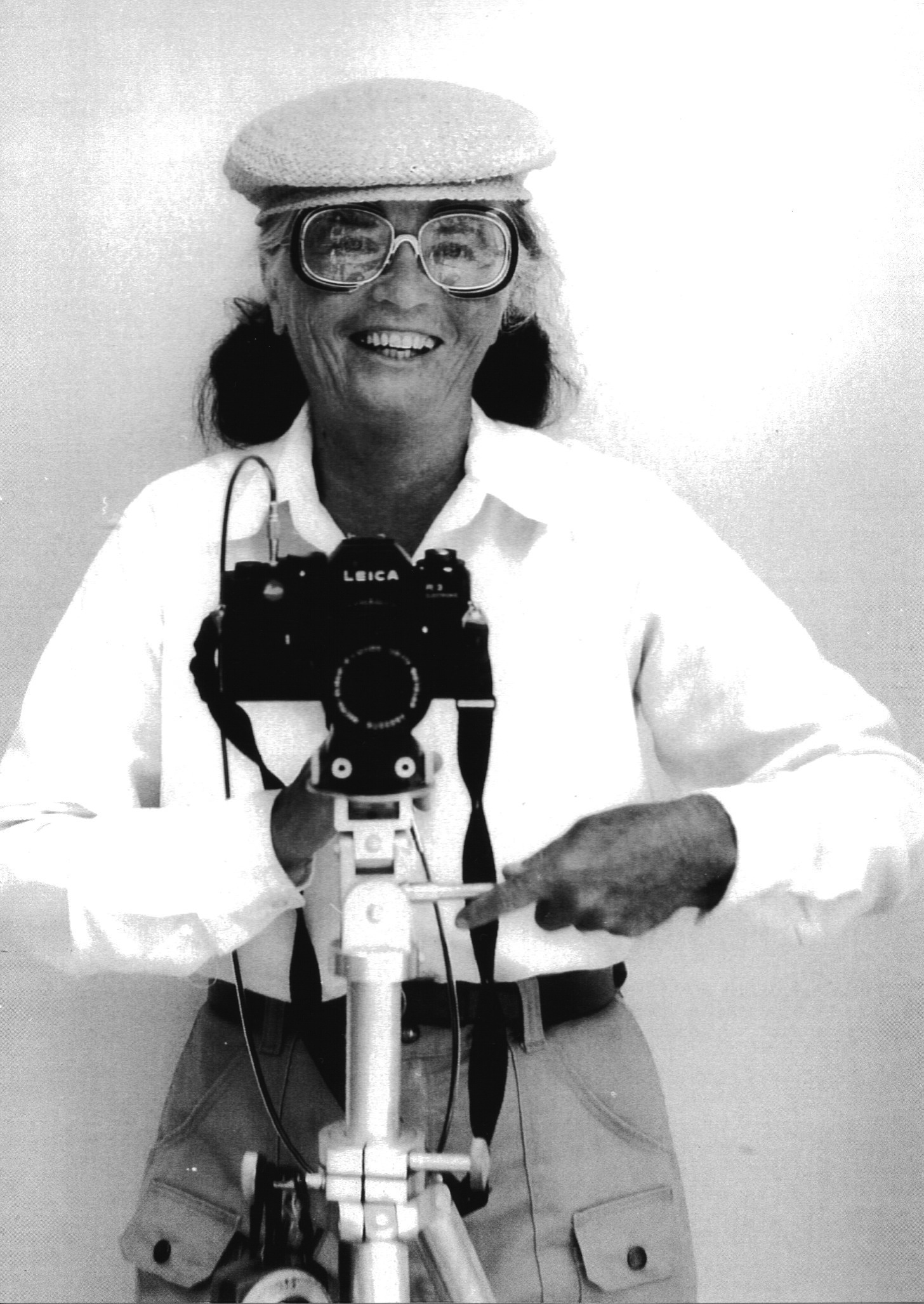

Maggie Foskett (Brasilian-American 1919 – 2014)

Camden artist Maggie Foskett dead at 95

Pioneered creative photographic technique called cliché verre

The artist Maggie Foskett died Dec. 1 in hospice care near her winter home in Sanibel, Fla., after a brief hospitalization, surrounded by her husband, son and daughter. She was 95.

Foskett, a summer resident of Camden, Maine, transformed bits of nature into brilliantly colored and spare, sometimes haunting shapes through a pioneering photographic technique known as cliché verre, the direct exposure of compositions onto photographic paper through an enlarger. She was among the first American artists to use cliché verre in photography and is credited with helping establish the technique as a photographic art form in the United States.

She exhibited at galleries and museums throughout the East Coast and her works are included in the permanent collections of the National Museum for Women in the Arts and the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, D.C., and in the Farnsworth Museum of Art in Rockland, Maine.

She had more than 25 one-women shows over her lifetime and in 2000, Foskett was included in “Photographing Maine 1840-2000,” a published compendium of Maine’s most significant photographers. In 2013, she was included in “Maine Women Pioneers III,” a collection of Maine’s best women artists.

“A sensitive and exacting observer, Maggie Foskett reveals nature’s incredible variety in new and surprising ways as she penetrates the internal structure of birds, plants, insects and reptiles,” a curator wrote of her 1998 exhibit at the National Academy of Sciences.

Born Margaret Edna Hughes in Sao Paulo, Brazil, on Nov. 15, 1919, Foskett was the first child of Edna and Reynold King Hughes, an American couple who relocated from the United States to South America for Hughes’ cattle ranching business.

Foskett completed her early education at the Sao Paulo Graded School, founded by her father, and matriculated to Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania in 1939, majoring in English.

Bryn Mawr College remained an important touchstone throughout her life, and she credited its faculty for instilling the belief that she could pursue her own interests at a time when women were expected to adopt traditional roles.

Foskett’s first marriage ended in divorce and she married her second husband, John D. Foskett, a Chicago businessman, in 1962, ultimately residing in the Chicago suburb of Geneva, Ill.

Foskett began her artistic career working with stained glass. At the age of 57, she enrolled in a community college course in photography and began shooting and developing black and white film.

But she became enthralled by the brilliant colors made possible by Cibachrome photography, and started working exclusively in color even though the medium had not yet been embraced by critics as a legitimate photographic art form alongside black and white photography.

At her second home on Sanibel Island, Foskett photographed tropical plants and sea shells, always at close range, and developed the images into 18 x 24 inch Cibachrome prints, magnifying small objects into larger than life works of art.

“A rag picker of small cosmologies in nature,” she sometimes called herself.

In 1984, Foskett moved from Illinois to Camden, Maine, and her career blossomed when she found a community of artists associated with Maine Photographic Workshops in the nearby town of Rockport.

Foskett studied photography with many of the best American photographers, including Ansel Adams, Sam Abell, Marie Cosindas, Ernst Haas and Jerry Uelsmann.

She discovered cliché verre by accident when, working in her darkroom in Florida, she turned on her enlarger and saw the translucent outline of a spider magnified on the photographic paper below.

She began experimenting with what she saw. She took tiny bits of plants and insects, created an arrangement between two glass slides, and exposed the slides through the enlarger directly onto photographic paper.

The resulting images revealed intricate details and variations of color unseen by the naked eye. The idea of unmasking the hidden beauty and mysteries of tiny pieces of nature fascinated her for the rest of her life.

In dragonfly wings, she found honeycombs. In plant stamen, she found snowfalls of pollen. In flower petals, she found rainbows of color.

She discovered that even rocks, cut thinly, could be shot through with the bright light of her enlarger to create extraterrestrial landscapes.

Through her many years of work, Foskett noticed the patterns of life’s building blocks repeated themselves in nearly every object she photographed. She remarked that she also came to understand the fragility of nature; some compositions of flowers or insects might fade so quickly she had time for only one or two images.

Foskett told one interviewer that her goal was to “show how delicate our balance with mortality is.”

She stopped using her camera completely in 1995, devoting all her energy to cliché verre prints made from her enlarger. In her most productive years, Foskett worked 10 to 12 hours a day in her darkroom, shredding images that failed to deliver their promise and sometimes emerging with only one good print for the day.

Late in her career, she became fascinated with x-rays of injured birds and animals, and composed images that superimposed natural objects onto the skeletal traces revealed on the x-rays.

She experimented with human x-rays, too, usually her own. One of her most memorable images shows blades of grass layered over an x-ray of her thigh, with the caption, “and then my bones will hold the seeds of summer grass.”

Foskett took one detour from cliché verre. In 2004, she created an exhibit out of a series of old black and white photographs she shot in 1979 at a shuttered institution for “wayward girls” in Geneva, Ill., dating to the late 19th century.

The photos included images of marked and unmarked graves on the grounds of the institution, known as the Illinois State Training School for Delinquent Girls, and the abandoned buildings that housed thousands of young women, many of whom died in childbirth while incarcerated.

The simple headstone of one 20-year-old girl, Sadie Cooksey, captivated Foskett and became the title of the resulting exhibition, “Who was Sadie Cooksey?”

She dedicated the show to “all the Sadies, past and present, who walk alone, sadly troubled.”

Physical limitations prevented Foskett from creating new artwork in the last decade of her life, but she found other interests to feed her creative mind and love of nature.

In Florida, she raised zebra longwing butterflies in her screened porch, tending the delicate chrysalises and delighting when the new life emerged. In Maine, she enjoyed feeding chipmunks from the palm of her hand on her back deck.

“She never really stopped,” said her husband, John Foskett.

Foskett remained an inspiration to dozens of artists and photographers, including her niece, the Vermont artist Sally Linder, and her stepdaughter, the Florida artist Lynn Foskett Pierson, and her unique body of work continued to be featured at galleries and museums. The Caldbeck Gallery in Rockland, Maine, represented the artist and her work.

Foskett’s last exhibition was at the Boston Children’s Museum in Boston in 2012-2013, and was titled, “For We Are All Sprung From Earth And Water.”

After cremation, Foskett’s ashes will be spread at her cemetery plot in Camden, Maine, at a time to be determined by her husband and children.

Foskett is survived by her husband, John Foskett; her daughter, Kate O’Neill; her son, Kenneth Hughes Foskett; her stepdaughter, Lynn Pierson; stepson, Chip Foskett; and five grandchildren: Liam W. Foskett, Robert W. Foskett, John Foskett III, Annie Mayers and Laura Pierson.

Foskett’s only sister, Dorothy Conklin, predeceased her in 2013.

In lieu of flowers, a charitable contribution in Foskett’s name may be made to: CROW, Clinic for the Rehabilitation of Wildlife, Sanibel, Fla., www.crowclinic.org/support-us/memorial-gifts.