Alan Bray at Garvey Simon Art Access

Review by Tatiana Istomina

May 23rd, 2014

Alan Bray could be a character in a Henry James novel: a New Englander who traveled to Europe and found himself profoundly changed by the experience. Born in Waterville, Maine, in 1946, he grew up in Monson, Massachusetts, studied at the Art Institute of Boston and the University of Southern Maine, and in 1971 went to Florence to enroll in a Masters program at Villa Schifanoia Graduate School of Fine Arts. According to the press release of the show now on view at Garvey Simon Art Access, Florence presented Bray with three treasures: a new painting medium (casein tempera), the examples of the Italian masters (Fra Angelico, Pietro Lorenzetti and Simone Martini), and a renewed and growing attachment to his native New England.

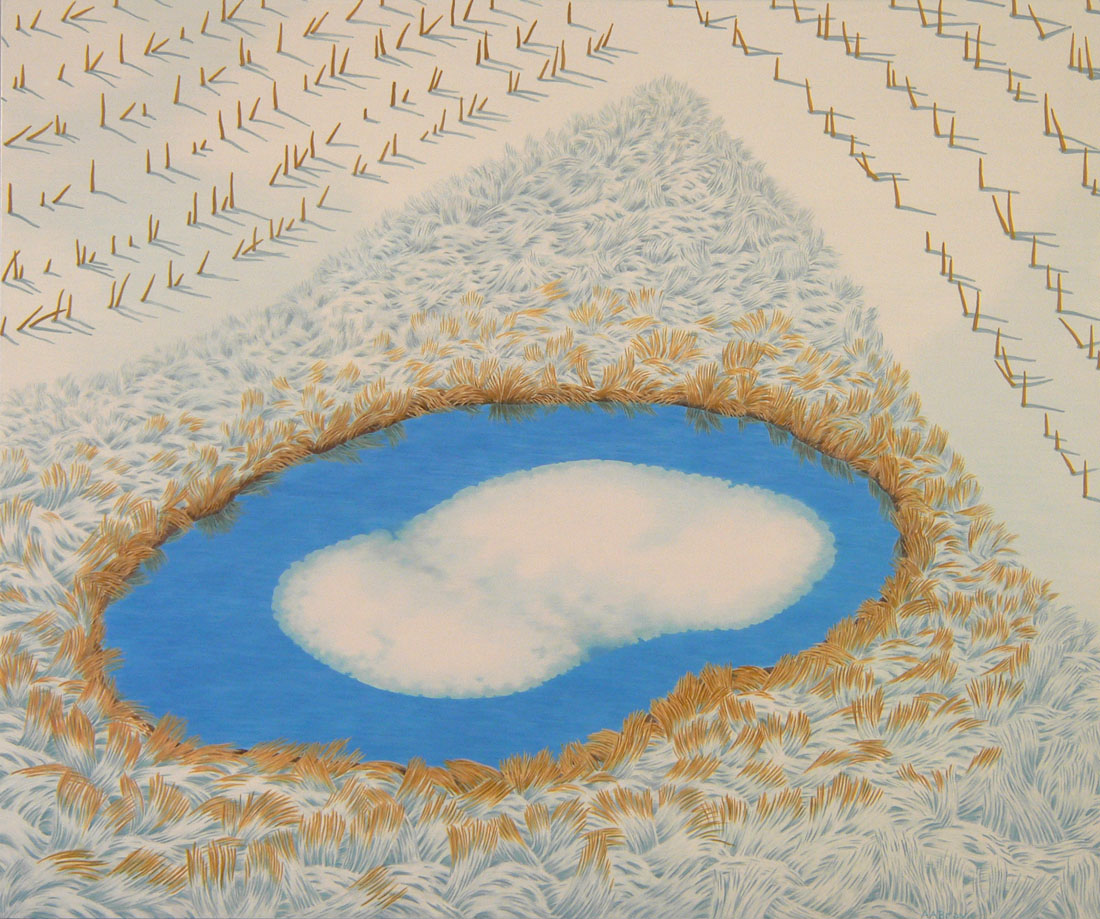

Wystan Hugh Auden referred to Henry James as the “Master of nuance and scruple”. The phrase appears to be an apt description of Bray: his small-scale landscapes at Garvey Simon suggest a highly sensitive, delicate and conscientious artistic disposition. The landscapes are the tranquil views of inland Maine: a footbridge over a small creek in the snow-covered woods, a field criss-crossed by diverging paths, a cloud sitting on the top of a hill. The paintings are made with casein on panel, and when viewed at a close range, their dry surfaces display intricate networks of closely-knit brush strokes. The depicted landscapes are highly simplified: all accidental details eliminated, all shapes reduced to their closest geometric analogs, organic chaos organized into geometric pattern. The apparent simplicity of the images, combined with the traditional subject matter and the unabashedly pleasing colors would have brought these works dangerously close to illustration – if not for the sophistication of Bray’s technique. The intense, slightly bizarre effect produced by these works is partly due to the dissonance between the ostensible prettiness of the images and the the formal austerity, even harshness of the method of painting used to create them.

The best of the paintings on view are posed exactly in the midpoint between the figurative and the abstract: the regular shapes that look like Plato’s ideas of trees, logs and ponds are organized with the precision of a mathematical proposition, while a few details supplied by the artist’s sharp observation of nature link these shapes to the reality of the tangible world. Such perfect balance is very hard to achieve: a work that strays too far into the world of ideas tends to turn into an abstract pattern. On the other hand, if it moves an extra step into the opposite direction, it runs the risk of becoming an inert and somewhat mannered landscape. The best piece in the show, “Winter’s false start,” finds an exact equilibrium between the observed reality and the mental diagram. The effect is striking and slightly disorienting: like the duck-rabbit figure, the image is perceptually ambiguous, oscillating between a pond in a field covered with snow and an abstract composition in white, blue and yellow.

This is also the piece that makes the viewer stop and ask herself – what could be the meaning of this work? The visceral pleasure produced by the painting is baffling and demands explanations. Surely, a serious art practice, especially one that has been sustained for over four decades, is an expression of a vision, of the artist’s understanding of the world – but somehow it has become rather difficult today to think of landscape painting as a vehicle of meaning. Bray’s works are going against the grain of contemporary painting and perhaps even contemporary sensibility – but they have a strong quiet presence, which indicates that something important is being said. What it is exactly, is hard to put in words. Perhaps they suggest that there is some kind of innate order in the organic chaos of life, a deeply ingrained law of clarity and perfection. Finding a rational order at the heart of reality might have been a difficult task for Italian Renaissance painters, but for an artist working today it is an almost impossible feat. Moreover, this is the task that cannot be achieved once and for all: with every new scene and every new painting the artist needs to start over again – but when his search is successful, life has a bit more order in it.